By Christina Papaleo, Staff Assistant to the Chief Diversity Officer

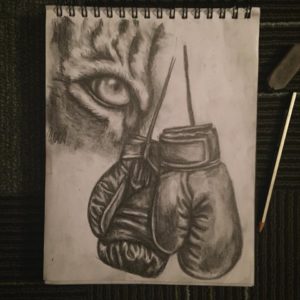

Drawing has always been the one thing in my life that never feels “disabling.” Despite criticism and comments I would receive for “being able to draw so well even though I had a visual impairment,” I knew that it could potentially be a place where I could find strength in my weakness. I hid in my sketchbook from preschool until high school, when I began to realize…as I shared my drawings with others…that what society calls “undesirable” (which is the short definition of “imperfection”), creativity calls remarkable. Advocacy and creativity called me out of the prison of “someday,” and that is where I found my purpose.

The more dependent we become on the words that people use to describe us based on what they see, the more uncertain we become of the truth that is inside of us that guides us into the life we are meant to live. Even as a student, I held onto that narrative of “not enough,” which led to an obsession of physically changing who I was–or punishing myself for who I was not. I thought looking perfect would be my all-access pass into acceptance and belonging. In retrospection, that insatiable hunger for perfection was nothing more than an all anxiety-inducing prison that kept me from braving what I was meant to experience.

I had a choice to make, and while I leaned on others to guide me to the “right” path, it is was ultimately something I had to do on my own: whether or not I wanted to hide from the world, or show it a new way to see.

Eventually I made peace with the idea that my greatest contribution was going to be hidden behind my greatest fear. Instead of fabricating perfection and thereby faking my identity, I had the opportunity to bring uncertain opportunities into physical realities through the same method I used to hide from a world where I felt rejected. My sketchbook.

Sometimes our most hated imperfections, which dwell in realms of uncertainty, lead us to our most desired opportunities. Drawing has always taught me that comfort isn’t courageous. The bravest place we will stand is in our own weakness. When our relationship with uncertainty is rooted in acceptance, we find it easier to make peace with change. When our relationship with uncertainty is rooted in denial, we find it difficult to see change as the path to growth. My blind side wasn’t meant to be a tool of hiding, but a teacher of healing.

My disability influences my creativity; it does not define it. I never draw out of sight (how people see who I am), but I always draw out of vision (what I believe about who I am and what I’ve been given). I do not think it is a coincidence that I returned to campus before I was able to reach one of my greatest breakthroughs… the moment where the “not enough” narrative was re-written into the “come as you are” story… receiving a prosthetic eye. It didn’t give me physical sight, but through this process, I realized that it was what I wanted my whole life. Freedom in my blind side and not from it …because it’s a creative gift that’s more life-giving and spirit-freeing than anything I could ever strive for.

The greatest prison that I could be freed from was the one that I put myself into. I learned that art is a way for us to connect and that we are all holding a part inside of us that wants to believe that vulnerability is not weakness. When we’re vulnerable, we take the risk of being criticized. But I believe that criticism is a hidden cry for connection.

I am an advocate of imperfection. I don’t want my story, or anyone else’s story to remain in silence–and now I am in a season where I don’t want it to serve as a place of resentment. We all have a blind side to brave.