By Lydia Polche

When you think about what makes a book memorable, it usually comes down to a mix of plot, characters, setting, and the familiar tropes you’ve come to love (or love to hate). Maybe you can’t resist a good forbidden love storyline, where the main lead can’t be with their lover due to agitating external influences. Tropes are familiar, fun and feel like stumbling across gold when you recognize them in a new book. However, modern storytelling is starting to forget that balance. When a book leans too heavily on its tropes rather than using them as just one part of a richer whole—we’ve got a case of tropefication.

The word “tropification” looks needlessly complex at first glance. The root word “trope” combined with the “-fication” suffix is certainly an odd pairing—at least, that is what I thought when I first stumbled upon the term out in the wild. I was scrolling through the formerly named Twitter when I suddenly realized just how long I had been mindlessly scrolling, only snapping out of it after coming across a series of tweets on my timeline. It was from an account I followed, passionately ranting about the supposed damage tropification has done to modern storytelling. Looking past their frustration-induced typos, I didn’t find myself enraged by the concept, but I was intrigued enough to dig deeper. Was tropification truly ruining stories, or was it just another internet-fueled exaggeration meant to snootily scold people about what true literature is?

It is hard not to come across as some book elitist when it comes to this topic. After all, criticizing the way stories are told can easily slip into pretentious territory. But at its core, the discussion around tropification isn’t about dismissing popular books or looking down on certain genres. It’s about understanding that storytelling has become increasingly reliant on familiar patterns and the impact it’s having on readers.

So, what exactly is tropification? Simply put, the tropification of books refers to the centering of a single theme or trope in storytelling. Tropes themselves are elements of storytelling, recurrent motifs employed by authors to create familiarity and structure. They’re nothing new and are present in a lot of media outside of literature. A common trope in action movies is the “chosen one,” where an ordinary character is revealed to be destined for much more and is typically tasked with saving the world (think Harry Potter). Other common tropes may be enemies to lovers (think John and Pocahontas in Disney’s Pocahontas), damsels in distress (any movie or tale ever), and many more. Tropes themselves are harmless and even aid in storytelling. But with tropification, there’s a shift where tropes aren’t tools to the story but are the story.

A great example of book tropification is Iron Flame (2023) by Rebecca Yarros. In most discussions of this topic, this book will inevitably come up as a prime example of tropes taking priority over actual storytelling. Iron Flame is the sequel to the positively received Fourth Wing, released just a few months before its predecessor. The first book introduced Violet Sorrengail, a young girl in a dystopian society who navigated a well sculptured world filled with dragons, an elite academic setting, and intense survival stakes. The “enemies to lovers” trope was present, but it was one element woven into a broader and compelling narrative.

The second installment, however, has been dubbed a victim of tropification. In her essay “Are Tropes Ruining Books?” Archisha Pathak writes that Iron Flame “seemed like it was put together far too quickly: a mix of clichés and basic plotlines thrown into print without much editing taking place in between.” The rushed feel Pathak describes reflects how the book relies on predictable elements rather than nuanced plot or character growth. It feels less like a unique sequel but more of a patchwork of familiar literary shortcuts.

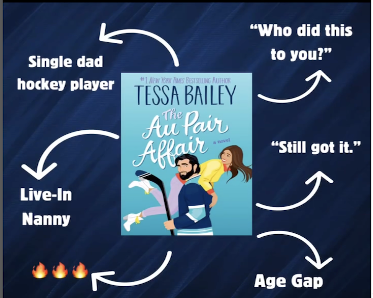

Tropeification is not just a storytelling issue but also an increasingly used marketing tactic. Last year, I even came across a photo of the first pages of a book that included a list of its featured tropes, almost like a directory. Some are so niche and so hyper-specific it comes off almost satirical. Authors have even taken to listing tropes in their marketing campaigns like the tropes are what truly matters. This shift creates a reader who is shaped by tropification’s promise of immediate payoff. Remember Yana? If not, she went viral on TikTok for frantically flipping through Six Of Crows by Leigh Bardugo, fussing as she searched for specific scenes BookTok made noise about. Her bio, “If it’s not smut, I probably won’t read it” perfectly personifies the kind of reader tropification is creating. It is one who reads for instant gratification rather than story. Examples like hers highlight just how hollow and repetitive modern storytelling is becoming under the weight of trope-driven expectations.

The appeal of a book leading with tropes isn’t lost on me. Who doesn’t want to know exactly what they’re getting into? Books are a commitment as they can be as thick as dictionaries and yellow-page phone books. Nobody wants to reach page 60 of some book they’ve only been barely tolerating just to find what they wanted was never there. But this semi-blind quality to reading is what reading is about. Reading involves discovery and being open to every universe a book wants to take you to. Limiting yourself solely to tropes you like and are familiar with for instant gratification stunts that experience. You could be tossing aside a book you might have loved simply because you’re too hellbent on finding a male lead that fits the misunderstood bad boy trope or because it doesn’t take place in a high school setting. Or, like Yana, it doesn’t include smut.

Tropification in modern publishing mirrors the fanfiction model. Sites like AO3 (a very popular fanfiction site) are known for their tag categorization. Adopting this in publishing churns out stories that are categorized primarily by tropes and tags rather than plot or literary merit. In fanfiction, this system works because readers seek out specific dynamics, relationships, or scenarios they already love. However, when you transfer that over, commercial books risk becoming mere packages of empty wish fulfillment. The only goal becomes to deliver expected tropes rather than crafting a compelling and original narrative. This shift blurs the line between published fiction and fan-driven content, prioritizing immediate gratification over storytelling depth.

The biggest downside to approaching books through a tropeified lens is how it can dampen complex narratives and cause readers to overlook the emotional weight of a story. Let’s say you’re searching for novels that depict the grumpy/sunshine dynamic, an amusing trope that depicts a couple that doesn’t make sense on a surface level. Your trope hunt might lead you to the novel We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver, which follows a mother left with the aftermath of her son’s mass act of violence against his classmates. The event leaves her isolated and a stranger in a town she used to call home. Readers solely interested in tropes might focus on the way that the relationship between Eva and her husband exemplifies the grumpy/sunshine trope: Eva is sharp and extraordinarily cynical while her husband is more easygoing and naively optimistic. Their relationship is an unexpected yet entertaining contrast given the serioussubject matter regarding their son. But someone focusing solely on that aspect of the novel would be missing its deeply introspective commentary on topics like motherhood, societal expectations of women, and the isolation that comes with not fitting neatly into those roles.

Tropification, in short, trains readers to approach literature like a checklist rather than an experience. However, we shouldn’t reduce complex stories to surface-level dynamics that were never meant to stand on their own.

Look at me now. I’ve become that Twitter user (with less profane language) ringing the bell about the downfall of storytelling due to tropification. But I promise this isn’t a manifesto telling people what to read and enjoy. Literature can be a vehicle to better understand the world and yourself. It can bridge together the unintelligible thoughts or feelings that are often hardest to articulate. It can also, at times, serve as a form of escapism that allows us to take our minds off the state of the world. Just be more open-minded and aware of how tropification may be shaping the way you engage with literature. When we start expecting everything to deliver instant gratification or fit neatly into categories, we risk missing out on the messy, unpredictable, and often more rewarding parts of the experience of reading. Not everything worth your time comes with a trope tag.

Works Cited

Dye, Eleanor. “Tiktoker Sparks Debate after Asking Why Book ‘Has so Many Words on the Page.’” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 20 Aug. 2024, www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/booktok-books-tiktok-debate-yannareads-b2598776.html.

Pathak, Archisha. “How Tropes Are Watering Down Modern Literature.” The Michigan Daily, 1 Feb. 2024, www.michigandaily.com/arts/books/are-tropes-ruining-books/.

Lydia Polche is a current SUNY Cortland undergraduate majoring in English and minoring in Professional Writing. She previously was a staff writer for APN, a publication based at SUNY Plattsburgh, and is currently a contributor to the first issue of Emblaze. She has a deep love for reading and enjoys exploring how words can articulate the inexpressible.